What Great CTOs do Beyond Technology

This article is aimed at new technical leaders of large or growing organization, who are looking to expand their leadership and functional skills beyond a mastery of technology. I have been working with organizations to help them adopt cloud computing for a little more than 7 years now. I was reflecting on what my team and I had achieved in 2020. I observed a few things that were surprising. Over the year we had proposed to our customers several initiatives to reduce the cost of operations, improve security and reliability, and use data and machine learning to improve customer satisfaction. While a few initiatives were taken up by our customers and we worked with them to implement them, several did not. The reasons for an initiative to fail or succeed had very often little to do with technology. In this article I want to explore what I learnt from the technical leaders of successful organizations and initiatives, about things that don’t have anything to do with technology.

The best reasons I’ve heard would be: (a) we need to do this other thing first to be able to do what you suggest, and we are working on it; (b) the benefits of this does not outweigh the cost or risk to us. These are well thought out reasons and I am glad many of our customers are making decisions that are right for their business. However, quite frequently, while our customer stakeholders agreed that our proposal made sense and should be done immediately, they were unable to do so.

I’d find senior technologists, including CTOs, say to us, “This is a good idea. We’d like to do it, but…”. The reasons given were specific to the situation but generally fell into the following buckets:

- We can’t convince “business” to make this a priority.

- We don’t have time/people/skills to do this.

- We have several fires burning now; we will look at it after that. Unfortunately the fires never seem to stop.

Some CTOs seem to be frustrated by an inability to implement technical changes that they themselves believe strongly in, and blame it on a seemingly ignorant “business”. However, I’ve had the good fortune to have met others who seem to be able to implement large scale, long running technology initiatives successfully. I’ve heard several tips and tricks from them.

I believe most CTOs are well-equipped to make technology decisions, but not every CTO pays attention to the non-technical aspects that successful CTOs seem to do. In this article, I try to group their tips and tricks into categories and patterns. In particular, I will talk about only non-technical aspects.

You may have noticed the quoted term “business” above. Technology functions often think of themselves as the special “technology” function and everyone else as “business”, as if they were somehow not part of the business. An analogy would be the hippopotamus in a zoo classifying every animal in the zoo as “thick-skinned water-loving animals” and “others”. I have been very guilty of this before and I understand this is a tempting and easy attitude to adopt. It is, IMHO, unproductive and wrong.

What is a CTO, anyway?

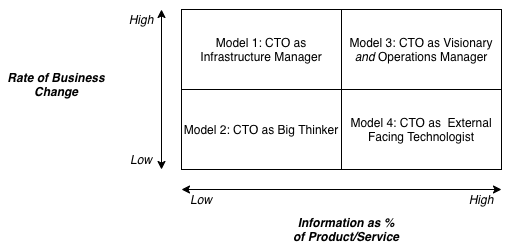

Before we begin, I believe some clarification about what I mean by “CTO” is required. Today, just about every startup, especially tech startups, has a CTO. It seems unimaginable, in some circles at least, to not have a CTO in a company. However, this was not always the case. The CTO role was rare before the 2000s. Up until the 90s, organizations had titles like “Head of R&D”, “Head of Engineering”, “IT Director”, and “Chief Information Officer”. As the role of technology in organizations grew, the role of the CTO started appearing and now is more common. However, it is one of the most ambiguous CxO roles. The “CTO” of every organization seems to have a unique mix of responsibilities. Dr. Werner Vogels, CTO of Amazon.com wrote an article about the history of the CTO roles, and points to a paper giving a classification quadrant. Considering these, there are two dimensions I look at:

-

What is the rate of change of the company’s business model? High: technology decisions that support the company’s business model must be centralized for consistency and speed; therefore, the CTO will have greater execution power. Low: business units and lines can optimize their own operations over long, stable periods; the CTO will be an “influencer”.

-

What proportion of the company’s product or service is captured via technology vs something else. High: the company needs someone to look beyond the horizon for big changes in technology so as not to be blindsided; the CTO will primarily look “outwards” and “forwards” at trends in technology and industry. Low: the company needs someone to optimize existing technology more than adopt new technology; the CTO will look “inward” at operational aspects.

Based on where an organization stands on these two dimensions, I classify the CTO role into 4 models:

In the rest of the article, when using the term “CTO” I will be referring to the Model 3 CTO. They are both “Big Thinkers” and executors. The business model may change rapidly and technology must keep up or stay ahead. The CTO must be able to execute and have authority over technical decisions, and will often have sizable teams. Technology is the product or at least has a huge impact on the cost and quality of the product. The CTO is not just an optimizer but a bringer of new ideas and a “big thinker”, and plays an important role in ensuring the business remains competitive.

Some organizations have both a CTO and VP of Engineering role. Here, the CTO makes technology decisions and influences architecture, technical standards, and change management.The VP of Engineering does people management, hiring, career growth of engineers, and general organizational health. The VP may report to the CTO or be a peer.

Visionary-Executor CTOs, with or without a VP of Engineering, have to get things done by other people, to grow their organizations. They are directly or indirectly responsible for:

- Setting goals and defining what good performance looks like;

- Giving people feedback on their performance and suggesting growth areas;

- Work with other functions and CxOs to define direction and then implement decisions.

The non-Technical Aspects of Being a Successful CTO

While CTOs, of necessity, work mostly on and with technology, there are a few other things successful CTOs pay a lot of attention to:

- Working with “business” (that term again): successful technology functions work hand in hand with the non-technology functions. Engineers often refer to everyone else as “business”, and talk about “business decisions”, as if they were somehow separate from the business and had no role in such decisions. This is a shame. Successful CTOs don’t see things this way. They see themselves and their function as an integral part of the organization.

- Running technology “as a business”: technology is not just software development, and software development is not just agile. Successful CTOs understand that the basics of business—cost, results, contribution to profitability, productivity—applies to the technology function just as to every one else. They see their function through a business lens, while respecting its unique characteristics.

With that said, here is what I’ve learnt from Visionary-Executor CTOs about running a successful technology function.

Work Well With Other Business Stakeholders

Many CTOs spend a lot of time looking internally to make and implement technology decisions, and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of their organization. However, there is a limit to how efficient you can make things. To grow a business, one cannot merely be shaving off costs and increase the speed of delivery. One must find new products and features, new geographies to expand into, and even entire new markets. This is as much the responsibility of the CTO as a CEO, COO or CMO.

To be able to do so, successful CTOs allocate time to develop relationships. They come in three flavors.

First, CTOs spend time with the other CxOs. They are eager to learn their “lingo”, what makes other functions tick, and what keeps them up at night. They not only ask to be included in meetings that have nothing to do with technology and listen actively, but also will frequently have spontaneous, unscheduled or “outside work” interactions. Such interactions lead to trust at a personal level. When making tough decisions where judgment and “gut feel” come into play, your peer CxOs are more likely to support you if they know you through many interactions and trust your character, than if they’ve only observed you through the cold logic of powerpoint presentations (no matter how well thought out they might have been).

Secondly, CTOs have a personal network of peers outside work. They do this through attending industry events, “birds of a feather” sessions, and impromptu connections. They are constantly learning about how other organizations see the landscape. They gain the right to do so by sharing their own learnings with others.

Third, CTOs keep their nose to the ground. They do not just guide and coach, but also learn from their employees. They understand that those on the coalface are likely to be more conversant with new technologies and trends. They encourage their employees to think bigger and bring ideas to the surface. Not all the ideas are going to work out and many may be about doing the same thing better, but it is worth listening carefully for those 1% of ideas that will make a 100% difference.

Money talks. Talk money.

CEOs and CFOs explain to their board and investors how much money they plan to spend next year, or quarter, in terms of how this relates to growth or profitability. They get asked about the value of each function’s cost and whether it can be reduced.

Every business function racks up expenses. Overall, their contribution leads to the company making money and profits. It is easy to see the contribution of some functions to the profit, but it is often hard to see the contribution of technology.

Most CTOs think, most of the time, that they are doing a heroic job with limited resources and budget. Most non-CTOs don’t understand how tech spends money, and think tech spends too much. “Where did the money go?” is an explicit or implicit question in most CFO/COO/CEOs minds. Other common questions are “Why does X cost so much?” or “Why has our cost for Y gone up?”.

When speaking to non-CTOs about cost, Visionary-Executor CTOs avoid these traps:

-

Trap #1: trying to turn other CxOs into technologists. Most business stakeholders do not have the background, interest or time to understand your technology lessons. When talking about money, business stakeholders are judging the technology leader’s financial knowledge and credibility. They do the same with each other, so CTOs are not being singled out.

-

Trap #2: adopting cost categories that don’t make sense for technology. There are standard cost categories in business: labor (salaries), equipment, software licenses, consulting fees, travel, training and so on. If you don’t come up with your categories, then your stakeholders will ask you questions about categories that make sense to them, but which will seem random to you.

To avoid these traps, and to “talk money” with the best of them, I’ve seen CTOs do a combination of these:

-

Define your own cost categories in terms of the company’s key business operations or functions: there are no standard accounting categories for technology spending so you have to come up with ones that make sense for you. Categories aligned to the business or functional structure of your company work best.

-

Know what is unique to technology and not business. Not every technology spend can be attributed to specific business functions. Attribute them to functions that are understood to be important: e.g. development tools and platform for companies that rely on software development for growth; security and risk management for business that deal with consumer data.

-

Know your costs and causes of variance. Explain the costs in terms of company’s key business operations: (a) what share of spend is associated with a particular function, preferably revenue generating ones; (b) what increase in spending is due to expansion of some business operation or a new capability. It is not necessary to be extremely precise: reasonable estimates will suffice.

-

Know what costs can be trimmed. Investigate cost savings opportunities with technology and keep a list. When you need a new capability, implement some savings measures and redeploy resources to internal projects that your business stakeholders may not care about. Your CFO or CEO is presenting financial projections to the board for the next fiscal year based on the spend in the last few months of the financial year plus growth projections. If you ask for more unplanned funds just after they’ve committed some numbers to the board, they will not like you. Instead, well before the fiscal year ends, implement cost savings and redeploy them to improve operations. That way, when you propose new spending, it will be largely on new initiatives that makes sense to business, with less funding required just to improve technology that has no visible business benefit.

Create a Culture of Collaboration

Most technology leaders want to innovate. However, they often complain about a never-ending stream of requests that are tactical, leaving no time for revolutionary improvements. They also complain about constrained resources and budgets and skills gaps. Conversely, their “business” counterparts are genuinely baffled by why technology takes too long to deliver and costs “so much”. When technology breaks, they complain it does so too often.

It is all too easy for these situations to devolve into an “us-vs-them” mentality. Later in the article, I will talk about ruthless prioritization as a way to not get caught into doing only routine work but implementing strategic changes. However, in order for that to successful, there must be a collaborative relationship between technology and everyone else.

The first step towards having a collaborative culture is for the CTO, along with other CxOs, to define an organizational culture. This often starts with a high level list of “values” or “principles”. At this point, it is little more than a common language or terminology. The CxOs now have to go and talk, repeatedly, about their values to their own organizations. They need to be publicly seen to be espousing these values. One of these values should be something similar to Amazon’s Leadership Principle of Earn Trust. When your team members are having difficulties with another function, it is important for them to see you work with the leaders of the other function to work the issues out collaboratively. Then, encourage your team members to do the same.

Do not tolerate people who don’t follow your values but somehow get the work done. A common anti-pattern is to have a hero engineer, who is rude and dismissive towards others, sometimes even the boss, because they know they have unique skill or knowledge that the organization depends on. Such people do more damage than they bring benefits in the long run. Their attitude may prevent novice engineers from asking questions and learning, and encourage people to hide their mistakes or capability gaps.

Culture takes time and repetition to build and maintain. The amount of time is usually under-estimated and undervalued. The CTO and the other CxOs need to consciously spend time on an ongoing basis to propagating and maintaining culture, by example and also being explicitly vocal about it. It is easy to be vocal about a principle and then not following it. Every individual CxO will forget to exemplify a principle or lose an opportunity to do so. The CxO suite must agree that espousing principles visibly is important, agree to call each other out, support each other, and be forgiving to each other on exemplifying their principles.

Run Technology as a Business

Being a successful CTO requires not only understanding and implementing technology. It is also about running the technology function of the organization as a business unit, working in concert with the rest of the business. We’ve spoken about working with other stakeholders earlier. Here we discuss how successful CTOs apply business sense inside the technology organization.

Understand Your Role

People newly promoted to CTOs from engineering positions, and CTOs in organizations that have recently grown, often fall in a trap of trying to do the same work they were doing before. It’s a natural temptation for two reasons: first, to continue doing what one is already good at; second, the CTO may be the most skilled person to do the work right now. However, this prevents the CTO from doing what they are meant to do and that no one else is in a position to do; it also hinders the development of the team.

CTOs need to set goals and performance expectations, and then let the team do the work. They have to let people make mistakes and learn from them. CTOs should refrain from stepping in to fill a skills gap; instead, they should work to identify and overcome the skills gap, by coaching, getting their teams required training, and hiring new talent. Good hires rise to a challenge. CTOs should be explaining the goals, clarifying what good looks like, and giving frequent, respectful feedback when it falls short of expectations. The best CTOs find a good balance between only praising and only criticizing. Instead of praising absolute performance, they tend to talk about improvement (e.g. “the scrum velocity looks better this month than earlier”). They also point out room for improvement with empathy (e.g. “While the release velocity has increased, so has the rate of failed deployments. What is the cause? How can I help?”).

Dive Deep, Judiciously

CTOs fear losing touch with reality. Many were bitten by missing out on a developing crisis in their technology function. Therefore, new CTOs are often tempted to try to understand everything, and quickly find themselves overwhelmed.

The best CTOs do occasional deep dives. They learn how to ask good questions and focus on recurring, not one-off, problems. Once, they find a recurring problem, they go down multiple layers and across organizational boundaries to find the root cause. They do not stop with the first plausible reason that comes up but look at multiple possible reasons, and for each, ask why, over and over. This may end up with pair-programming with a developer for a while, or spend time debugging an infrastructure problem with your best systems engineer. The CTO then comes back up and makes technical decisions based on relatively hands-on knowledge. Of course, before making the decision, the CTO would have first formulated it as a hypotheses and checked-in with many team members and other stakeholders who’d be impacted by the decision, as a form of a “smoke test”.

What remains more of an art rather than a science is to know which problems to go deep into and which to trust your team to solve. CTOs should focus on recurring problems where the surface cause seems easy to solve, but remains unsolved for some reason. That indicates there is some underlying issue that your team cannot see or solve themselves.

It may help to let the team know what you are doing, otherwise the team may feel that you are micro-managing in the worst possible way–randomly and inconsistently. I had a mentor CTO who used to declare, loudly, “Hold on! Can I please try to solve this problem?” He had previously told his team that he would occasionally do that to stay sharp. They respected him the more for it, even though often it took longer for the engineers to explain the problem to the CTO than solve it themselves. The CTO would ask deceptively naive questions that would occasionally lead to an “a ha” moment, when the team had found a root cause for several issues or when they discovered the problem had a radically simpler, non-obvious solution.

Look Outside to Gain Perspective

It is healthy for a technology organization to celebrate its good work and successes. Initially, there are plenty of challenges to solve and creating anything that works is already an achievement. The talent in the organization is also new and their diverse perspectives allow solutions to be evaluated from multiple angles. The teams and leaders celebrate even small successes which keeps motivation high; the diversity of perspectives means they don’t ignore problems or issues, or start believing that the successes being celebrated means things are perfect.

However, soon, the organization’s perception of itself as doing a good job, and convergence of perspectives as the team grows older, creates a blind spot. In other words, the organization is in danger of over-estimating its competence and its product quality and under-estimating its issues and shortfalls.

Successful CTOs touch base with paying customers as much as possible to get an objective evaluation of the quality of their product and speak to peers (not directly competing with them) to get information on emerging trends and the state of the art. These two sources of information keep them grounded. They allocate a good chunk of their time speaking to outsiders, not insiders, to to remain clear-eyed and ruthless about reality.

Complement Your Instincts with Metrics

Great CTOs use a judicious set of quantitative metrics to measure key aspects of their function’s health, and use them to drive change.

Technologists understand metrics. For e.g., they use monitoring tools extensively to measure page load times, API latencies and error rates, CPU utilization, and so on. A mature technology team will have dozens of operational metrics to tell them about the health of their product.

What about the health of the process of building the product? Most technologists resist using metrics to measure the quality of their processes, while being perfectly happy using metrics to measure the quality of the output (i.e., the result of the process).

Most technologists belief building products is a craft and does not lend itself to measurement by metrics. Which developer has not shuddered at the thought of their productivity being measured by Lines of Code (LOC) committed?

In the book Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, the authors Nicole Forsgren and Jez Humble talk about practices that work and ones that don’t, and back up their conclusions with metrics. No one shudders at their metrics.

So, not all productivity metrics are bad. Some metrics are good for measuring how well you are doing. Now, metrics are not a substitute for understanding what’s going on. A metric can tell you if something is going wrong, but not how to fix it. A CTO must remain in touch with her people and with the architecture to guide her team to build good quality products. So, when and where should one use metrics?

Metrics serve two primary purposes:

-

Metrics can help establish objective reality. When a technology organization becomes big, it becomes difficult for the CTO to verify whether anecdotal information is correct or calibrated. Subjective and differing interpretations of problem indicators can lead to erroneous conclusions.

-

Metrics can help modify the behavior of individuals and teams to achieve tactical goals. They can be used to measure operational hygiene and by reviewing them, and nudging teams, the CTO can get teams to achieve larger, strategic goals.

Establishing a metric and tasking a team to improve it gets people narrowly focused on improving the metric itself. This can inadvertently lead to undesirable behavior, where people ignore the actual outcome and undertake actions to improve a metric when its no longer useful or actively harmful. Therefore, here is a distillation of various tips I’ve gathered from CTOs about metrics:

-

The metric should be measured with little or no effort. A metric that requires much manual work to capture leads to either waste of time due to people spending time measuring the work and not on the actual work, or to general unhappiness amongst talented engineers. I’ve seen CTOs allocate upfront time to develop automation for gathering metrics they deemed important, so their teams did not have to do it manually later.

-

The “why” of the metric must be communicated and over-communicated. If people don’t understand why a metric exists, the CTO may learn something from the metric but will find it difficult to get people to modify their behavior in the right direction. Great CTOs repeat the “why” many times and ask for feedback. They listen very carefully to situations where people are debating a metric’s definition or how it applies to them: those are signs the metric may need to be refined or its scope should be narrowed. When people understand the intent of the metric, they are likely to bring issues with the metric or the gap between the metric and what it is truly trying to represent to the CTO.

-

Review regularly. Actually look at the metric, and visibly use it to change priorities and make decisions. Use your regular management meetings to do so and don’t create a new one. When people know that the CTO genuinely cares about the metric, so much so that they are sacrificing some other item on their management meeting agenda, they will also pay attention. If people perceive that the metric is not something that is important to their CTO, they will become cynical and resist future attempts at introducing metrics. If every new metric comes along with a new review meeting, soon you will have no time to do actual work.

-

React to changes. If a metric is trending in the negative direction, do something. Do not accept face value explanations like “it looks bad, but everything is under control”. Work to get to the root cause, allocate time to new initiatives or projects, assign tasks and hold people accountable, and review again. Or, if the metric is genuinely mis-leading, remove it. When removing a metric, communicate clearly that the metric is being removed and why. This is also a good time to reflect on the reasons the metric was chosen, why it did not work, and lessons learnt from the experience. Choosing a metric that later did not prove useful is commonplace and part of learning; there is no reason to be embarrassed about it.

-

Celebrate improvements. If a metric is moving in a positive direction, do something out of the ordinary. Not a difficult, expensive or complex thing. (Reserve those for actual outcomes.) Simple things like a shout-out, donuts for the team, team lunch. All it takes is some kind of recognition that the CTO has noticed and acknowledges the work that went into improving the metric.

-

Be frugal with metrics. Introduce only one or two at any time. Let the team become comfortable with them. Relentlessly automate until it becomes effortless to measure and review. Relentlessly review until that metric becomes second nature to everyone. When you add a new metric, consider dropping an old one, explicitly. Too many metrics leave little time to discuss them in any depth, celebrate or react to, or sometimes even to remember their original intent.

Decode Business Demands and Prioritize Ruthlessly

Technology teams do a very broad range of tasks, but receive accolades for very few. Why? Because some “business requests” are more important and others are not. Successful CTOs develop a nose for finding out what the top business priorities are. It does not help to achieve a low priority objective very well, when the CEO or CFO is desperately looking for meaningful–if imperfect–progress on a higher priority objective. Knowing what is high priority starts with understanding as much about the business as possible, and asking “What would be the impact of this?” for each request. The technology organization must take an active interest in the impact of their tasks and provide inputs into prioritization. If they don’t, soon there will be a lot of “priority 1” tickets, where the requestor of each ticket genuinely believes their request is top priority. It is, for them. They can’t all be done together, though, due to limited resources. At that point the technology function will have to prioritize anyway, and since they did not seek to understand the impact and priority upfront, sub-optimal heuristics like first-come-first-serve, whoever-shouts-loudest, or whatever-is-easiest will be used. These methods may not necessarily prioritize what the organization really needs.

Successful CTOs also prioritize recurring problems. Not every problem is important enough to solve immediately. Two questions help to clarify the priority: (a) what is the impact of this each time it happens; (b) how often or how likely is this to happen. Precise answers are not always needed–approximate estimates are often good enough. Prioritization of competing demands needs to be done frequently. CTOs allocate more time to understanding the need than on detailed cost-benefit exercises (which are often based on imprecise assumptions anyway, so that value of extra precision is doubtful).

Develop Talent

Newly promoted CTOs, or CTOs in smaller organizations that are growing rapidly often pay most attention to technology, then processes, and then to people.

While good technology is important, mediocre technology can be improved or replaced by better technology, if there are good processes. To implement processes, and to implement the right changes, one needs good people. So, the CTO’s priority should be first people, then processes and then technology.

Consider that winning sports teams are made up of talented individuals, who are coached and developed, and who work well together. It is not necessary to have the best athletes–they are too few and too expensive. Good talent will do nicely, if they are coached and work well together. Good talent is on the lookout for development opportunities. On the other hand, a group of individually highly talented athletes who can’t play together won’t win matches.

Successful CTOs seem to have great engineering managers working with them, to help them scale themselves. Often, they are emerging talent they have spotted and coached.

While every CTO’s style of managing people is different, there are some common themes amongst successful CTOs. They seem to pay attention to:

-

Motivating people. Productive technology organizations seem to be full or highly motivated individuals, who feel their work is a mission. More importantly, when talking about technology decisions, they seem to have great clarity about not only what decision is to be made, but also why it needs to be made. Knowing why is a great motivator: it generates amongst people a satisfaction of doing good work to achieve outcomes, not (just) to earn rewards. Successful CTOs spend a lot of time thinking about and explaining why.

-

Developing people. Successful CTOs restrain themselves from doing their employees’ jobs for them. They dive deep occasionally, to stay in touch and learn about root causes, but generally set goals and performance expectations, provide guidance, and let people learn. They pay special attention to developing new managers, and coach them on how to develop their teams. They talk to their reporting managers on not just technical outcomes, but coach them on how to develop their teams to deliver outcomes and become better managers. CTOs who promote engineers into managers without spending time developing their management skills often complain about attrition, lack of skills, or having to get hands-on often. On the technology side, CTOs spend time thinking about the learning needs of their organization and implement a mixture of on-the-job mentoring and formal training to develop talent.

-

Hiring people. Successful CTOs seem to spend time deliberating what kind of talent they need in the organization. They develop good hiring practices and set standards. They tend to hire generalists who can learn, rather than people who are excellent in specific areas out of the bat but cannot learn new things. They implement processes to spread hiring guidelines and standards, give opportunities to new interviewers to shadow interviews, implement a review process and update guidelines from time to time. Most importantly, they know that hiring decisions should be made by the team (with the CTOs guidance on required skills and standards) and not solely by them. In this way, they strive to create a pool of interviewers who will hire candidates who are better than them and have diverse skills, allowing the organization to become better over time.

-

Planning talent. Successful CTOs seem to have a map of what their organization will look like tomorrow, based on their understanding of where the business is going. They design organizations around future needs. They resist changing organizational structures to suit a few rare talents. They are aware of their organization’s funding and planning cycles, and start socializing new initiatives and the head count needed for them with their fellow CxOs ahead of time. When the planning cycle arrives, they describe the organization structure needed to achieve future plans and leverage the previously socialized buy-in to get support from their peers for their head count requests. They also have a fallback plan (graceful degradation, if you will) if not all head count is given.

Conclusion

In this article, I tried to summarize what I’ve heard, observed, and been told by many CTOs about what they consider important–outside technology–into some kind of framework. I hope it gave you some things to think about.